How two dams in Sudan replenished villagers wells

A dry well and at the same time a green tree of the Mesquite species, Photo: MC

Mekki ELMOGRABI

Fashaga area along the Sudanese-Ethiopian border is famous for being the most fertile land in Gedaref state. In this area, soil fertility is vital for crops to thrive and influences their yield.

However, instability has affected agricultural activities in Fashaga. But in Gedaref state, it is not only instability that disrupts agriculture. Reliance on rains for agriculture coupled with poor water harvesting practices remains a hindrance in this area.

Mubarak Nour, head of the Gedaref Associations of Farmers and Landowners in Fashaga, says that the rain in the Gedaref area is usually hefty, even more than what is needed during the stages of preparing, seeding, and germination.

Whenever it rains, part of the rainwater runs off the surface into water bodies such as rivers, dams, and lakes; the other infiltrates the earth’s surface and forms groundwater.

But even without heavy rains now, residents of Fashaga and surrounding areas have had their water wells almost full throughout the year.

According to experts, this is attributed to the presence of Atbara and Sitait dams, which were inaugurated in the area in early 2017, targeting electricity production.

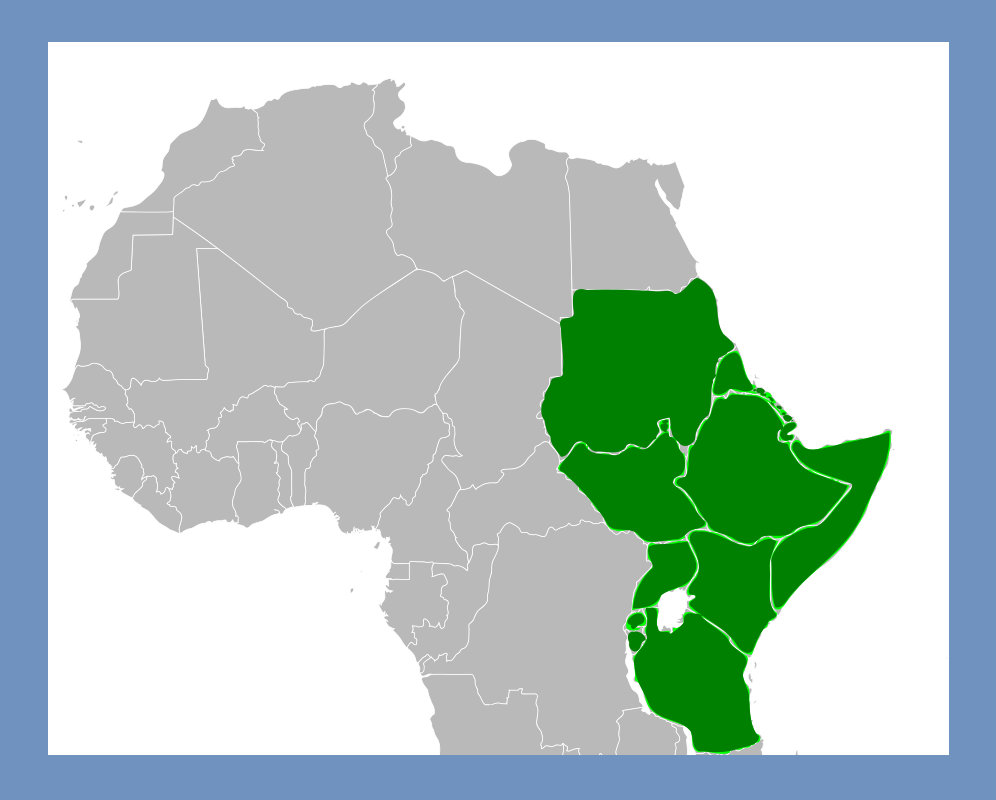

The dams are located at Upper Atbara and Sitait rivers, about 20 km away from the confluence of the two rivers, 80 km south of Khashm al-Girbah Dam, and 30 km away from Shuwak town, covering parts of Kassala and Gedaref states of east Sudan.

Upper Atbara Dam is 58 meters high, while Sitait Dam is 55 meters high. They connect at a joint channel to flow in a joint lake.

Residents say that when engineers told them that the two reservoirs were not mainly for irrigation, farmers were sad about that, but when the water of the wells in the surrounding communities increased, they started to learn better about the impact of harvesting water from the ground.

Nour says their wells are now “replenished constantly with underground believed to be flowing from the two dams,” enabling them to access drinking water, water for domestic use, and irrigation of their crops.

A study on the impacts of dams on surrounding groundwater levels indicates that “water inside a dam can cause the surrounding groundwater levels to rise,” with some of the positive effects being easing the extracting of water from the ground.

According to the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI), groundwater promises to close the gap between water supply and demand and buffering the effects of climate variability.

Groundwater is the most important source of drinking water for people, livestock, and wildlife in the 11 countries in the Nile Basin. According to the Nile Basin Initiative, an intergovernmental partnership of 10 Nile Basin countries, over 70 percent of the rural population in this region depends on groundwater. Groundwater is stored in aquifers.

One such aquifer in the Nile Basin is the Gedaref-Adigrat aquifer, shared by Ethiopia and Sudan.

To the residents of Fashaga, the lessons learned, and the increase in the water level in wells confirm the intended benefits of the Gedaref-Adigrat Aquifer Project of reducing demand on the water by using the aquifer’s water resources more efficiently and relieving pressure on other national and trans-boundary water resources where available like River Nile.

“After these two projects, I became a strong believer in the Gedaref-Adigrat Aquifer because those reservoirs enabled a considerable increase in the waters of the wells. It means the water table is full because the surface is full, and people can get water for agriculture even in the dry season,” Nour observes.

The Gedaref-Adigrat aquifer covers 52 square kilometers in Sudan and Ethiopia and is one of the three transboundary aquifers selected by the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI). The other two are the Kagera and Mt Elgon aquifers.

Abdalla Hassan, a farmer and businessman from the border town of Gallabat, says agriculture is not the only source of wealth in Gedaref. He points to cross-border trade as one of the critical sources of wealth.

“The income from cross border trade is high, but we need water harvesting project because rainwater destroys roads instead of being directed to reservoirs,” Abdalla says, adding that there is a need to conduct scientific research on water harvesting in the area to guide people on modern methods instead of the current traditional practices.

Experts in Gedaref observe that groundwater harvesting could help solve the water shortage permanently in the area.

Omer Al-Badawi, Director of Gedaref Water Corporation, says that the daily need for water is 45,000 cubic meters, but the current supply capacity does not even meet half the demand.

According to Eng. Al-Badawi: “The people of Gedaref have suffered from the water problem, but they will enjoy stability in the water supply if the Gedaref-Adigrat Aquifer Project is implemented.”

The Gedaref-Adigrat aquifer is one of the three transboundary aquifers selected as a case study under the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) ‘s Groundwater Project – ‘Enhancing Conjunctive Management of Surface Water and Groundwater Resources in Selected Transboundary Aquifers: Case Study for selected Shared Groundwater Bodies in the Nile Basin. The others are Mt. Elgon and Kagera aquifers, respectively.

The NBI project aims to strengthen the knowledge base, capacity, and cross-border institutional mechanisms for sustainable use and management of the three selected transboundary aquifers. It will also aid the national achievements and reporting of water-related Sustainable Development Goals and support environmental protection while enhancing the socio-economic development of the Basin’s population.

The five-year (2020 – 2025) project is funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) through the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and executed by NBI.

Mekki Elmograbi is a Press writer on African affairs, could be reached via email elmograbi@gmail.com and WhatsApp +249912139350

This article was supported by InfoNile with funding from Nile Basin Initiative.